When does the history of a city begin? The City of Vancouver answers this question by celebrating the 125th anniversary of its official incorporation this year. The City has politely acknowledged that other people were here long before the place was called "Vancouver," by including aboriginal participation in the festivities and performances. This is as it should be. However, how old is Vancouver then? What about the several thousand years of human occupation and culture before 1886? Is this past so vague and hazy that it is only peripheral to our civic narrative? Vancouver has a genuinely ancient past that its citizens deserve to know more about, well beyond this anniversary year. Specific ancient sites and cultural artifacts should be acknowledged and celebrated.

What exactly is ancient? Ancient refers to the very distant past, perhaps more than 1500 years old. By this measure, Vancouver seems new and not ancient. Many Vancouverites would also accept this assertion based on an inherited European disposition to regard ancient as something to do with Greek and Roman history. If you want ancient, you go to Rome to see the Coliseum. If you want ancient in Vancouver, you go the Central Library which is modeled after the Coliseum. Obviously this is fake ancient. Ask a citizen on the street where you can find a genuinely ancient location in this city. Gastown, with its lumpy green monument to "Gassy" Jack and his saloon of the 1880's, is not really a cultural Ur-site. Neither is the peripatetic Hastings mill building of the 1860's, relocated to a scenic park in Point Grey.

|

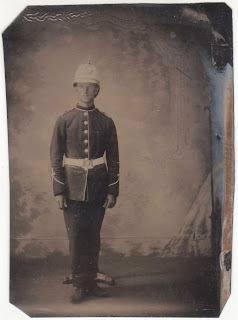

Ancient Midden in Stanley Park, 1888 (image: City of Vancouver Archives SGN 91)

|

There are numerous places in town that date from between 1500 to 4000 years ago, well before the Coliseum in Rome was a gleam in the eye of its architects. For example, there is the Marpole Midden site on southwest Marine Drive (under the Fraser Arms Hotel and parking lot). This contained acres of layered shell detritus up to 15 feet thick and 1000's of artifacts from an extensive village that existed for about 1000 years, from approximately 2500 to 1500 years ago (it may be much older). Numerous human burials were found here, including one enclosed within a 6 foot high pyramid of river stones, capped with what may be one of the oldest surviving sculptural objects made in this city, a stone figure bowl. This location at the mouth of the Fraser River, the largest in the province, made it one of the most geographically desirable on the entire coast because of its easy access to massive salmon runs and large quantities of shellfish.

There are substantial village sites of equal age or older at Jericho and Locarno beaches. Stanley park is filled with sites, including the shell midden and village of X'way X'way that stood near Lumberman's Arch. The last natives living here were unceremoniously kicked out in the 1880's and several hundred or possibly thousand years of midden deposits were dug up and used as paving material. These are just a few examples. Numerous artifacts from ancient sites like these have been re-buried in archival storage, invisible and uncelebrated in museums within this city and across the country.

|

| Stone Carving from Marpole Midden, circa 500 B.C.-500.A.D. (image: City of Vancouver Archives In P132.1) |

One difficulty in appreciating these ancient sites is visibility. They are not made of monumental heaps of stone, such as in Rome. They look different. Understanding the lay of the land and why certain spots were so appealing to ancient people is crucial. Another reason they are difficult to appreciate is that many of them have been obliterated or obscured by property development during the past 125 years. This stems from a combination of ignorance, greed, lack of respect, culturally biased ways of valuing history, and of course the perennially contentious issue of land title. Ignoring these sites helps to avoid uncomfortable questions and stifle conflicting narratives.

This remains an expedient thing to do, but it perpetuates a lie: Vancouver is new. It may be new as an incorporated civic entity, but it is not new as a place of human culture. This city has a history that is not being told to the general public and has remained the domain of a small group of specialists and stakeholders, such as archaeologists and local aboriginal communities. However, this civic history is relevant to everyone that lives here and everyone should have the opportunity to learn about it. We have an ancient history that deserves wider acknowledgment and celebration. We don't have to get on a jet to Rome to experience ancient. It's right here.

Sean Alward

published: Georgia Straight, November 22, 2011